I’ve long

wanted to visit Rio Azul Jungle Lodge, and the owners have been offering to

host me for an inspection visit for several years. I’ve just not had the free

time to follow up on it. But during the first planning stages of this current

private tour a year and a half ago, my clients did their research and asked if

I’d be willing to change my usual Mato Grosso itinerary a bit to add a few days

at Rio Azul. That didn’t take any convincing.

It’s only 39

kilometers (24 miles) from Cristalino Jungle Lodge the way the Bald Parrot

flies, but it’s amazing how different the habitats and resulting bird life is –

all reflecting a simple difference in geology. It takes nearly 3 1/2 hours of

travel to get there, starting with the boat ride from Cristalino Jungle Lodge to

the Teles Pires boat launch, where two taxis from Alta Floresta had been hired

by Rio Azul to meet us. From there we drove north to a ferry to cross back to

the east side of the Teles Pires.

From there

we drove in a zigzag fashion mostly northward through patches of forest and

many miles of cattle pasture (some of it the legacy of the former governor, now

in jail for corruption, as he used state-owned equipment to clear the land),

passing an active Jabiru nest, Burrowing Owls, and other birds that have

invaded the region in the past 30 years or so. Here are a couple Google Earth

screen captures that show the location relative to South America (southeastern

Amazonia, nearly in the center of the continent), and just NNW of Cristalino in

the state of Pará.

Rio Azul has

only seven cabins, and their idea is to stay small, hosting groups of either

birders or fishermen (but not both at the same time), and keep groups to about

eight people or fewer. The owners, Carlão and Ivani, have created a paradise

and continue to work here themselves, as guide, boatman, and chef. It was a wonderful

experience. The closed eyes and odd expressions in group photo here shows why one should always take multiple shots..

One main

attraction here is the Rio Azul river itself, a tributary of a tributary of the

Teles Pires (which itself is a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon). People can

fish here, but for the Komi family, a place to wade and swim was a draw (though

while the parents and I went birding on two days, the boys and the nanny went

fishing with Carlão).

One had to

watch for stingrays, and we did see a few. They’re not really dangerous as they

don’t bury themselves in order to ambush. You do have to watch where you walk,

but they are obvious and shy, swimming away before you can get very close as long as you’re not running through the water. The water here is unbelievably clear and

full of fish. The stingray diversity is surprisingly high (I think I heard

eight species) and hints at a very different geology millions of years ago when

there was a large inland sea connected at times to the ocean. The genus here is

Potamotrygon, which simply means

“river stingray” from ancient Greek (recall Hippopotamus, meaning "horse of the river," but then it makes me wonder about the quail-dove

genus Geotrygon, which must mean “ground

stingray”).

Two of the prize

birds that my clients hoped to see here are best seen by taking a boat ride on

the river, which we did our first morning. We passed the remains of a bridge that was demolished by the

Brazilian air force after the millions of square kilometers on the north bank of

the Rio Azul was declared a military reserve but only after settlers had already

built the bridge and started to clear the rainforest. So like Cristalino, Rio Azul

lodge is adjacent to one of the largest and best-protected continuous tracts of forest in the

southeastern Amazon.

The first of

the two targets was a fabulous hummingbird. Crimson Topaz is large, almost all

glittering red with a yellow throat, and possessing two elongated tail feathers

that cross and extend well beyond the other tail feathers. I don’t have my 50x

Canon PowerShot on this trip (in for cleaning and repairs), so this photo is

almost a joke. It does document my only lifebird of the trip as it was diving

down after grabbing an insect over the river – the two long tail feathers

point up, the bill points down.

The other

target bird, which we saw from the exact same spot in the river was a group of

seven Bald Parrots perched in a leafless tree by the river edge. Here’s a photo

of one I took at Cristalino Jungle Lodge in 2006, just four years after this

very strange species was first described to science (it was the first record

from there, where there are still only 3 or 4 records, straying from near here, no

doubt).

With the two

main specialties under our belt, we could relax and enjoy whatever new birds we

found – and there were plenty. We took three other boat rides, one in the early

morning before breakfast on a successful search for the elusive Zigzag Heron.

We had amazing views of it and raced back for breakfast. Here’s a video our

return on that trip to give an idea of what it’s like.

Surrounding

the lodge is some fine Amazonian rain forest (though we are here during the

winter/dry season and therefore no hint of rain). The early morning sun through

the canopy lit up this red-trunked tree beautifully. With the recent Scientific Reports article that lists 11,676 species of tree in the Amazon Basin, I will be lucky to eventually know no more than about 0.5% of them by the end of my lifetime.

Very common

in the taller forest was this vine, new to me. It is Heteropsis flexuosa, known as Titica (prounounced "chi-CHI-ca," and used widely for the

fibers in the aerial stem and roots. The family is Araceae, same as Philodendron and the familiar skunk

cabbage.

We had some

good birds in this taller forest, including at least three different Guianan

Gnatcatchers (or Para Gnatcatcher by some who split it), a very rare bird at Cristalino but much easier here.

Mixed flocks

had many of the same birds as at Cristalino (such as Chestnut-winged Hookbill

and Rufous-rumped Foliage-gleaner), but Rusty-breasted Nunlet seems more

regular here, as was Brown-banded Puffbird. This is one of two we saw and

several that we heard every day.

My friend

Brad Boyle identified this Voyria

spruceana for me. It’s in the family Gentianaceae and gets its nutrients

from underground fungi – though who knows if it gives anything in return or is

just a parasite.

Speaking of

fungi, though this is the dry season with not much around, I did find this

nicely dried out Lentinus crinitus,

identified using the downloadable fabulous new field guide by Jean Lodge and Susanne Sourell.

We saw several

of the really interesting birds here in a shorter forest as well as more open

scrub that grows on an isolated patch of very low nutrient white sand along the

entrance road – a feature that like the stingrays also harkens to an ancient

inland sea.

We had the

first local record of the widespread but patchily distributed Plain-crested

Elaenia, as well as a brief but good views of Blue-tailed Emerald. But I was

totally blown away when a pair of Rufous-crowned Elaenias popped up in response

to my recording and playback of an unknown vocalization, a quiet “grrrr” sound

from the scrub. A few hundred kilometers separate this occurrence from the

nearest other record, and I wasn’t even aware that the species occurred south

of the Amazon. I had seen it 17 years ago in the Gran Sabana of Venezuela and

then again just last year in the northern Brazilian state of Roraima. I got

recordings, which I appended to my eBird submission and can be heard on the

Macaulay Library’s website here.

The plants

in areas of white sand are fascinating. I especially took to the melastomes

here. This appears to be Sandemania

hoehnei, a real white sand specialist. The paper is Renner, Susanne S. 1987. Sandemania hoehnei (Melastomataceae; Tibouchineae): Taxonomy, Distribution, and Biology. Brittonia, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 441-446.

This is a Macairea sp., and though most of these

melastomes have very tough leaves, presumably for water retention, this one is

also unusual in having fewer than the normal number of primary veins running from

the base to the leaf tip.

But even

stranger is this Microlicia sp. with perfectly typical flowers but very tiny leaves folded down against the stem.

This

probable Remijia sp. in the family

Rubiaceae was notable in being stunningly fragrant, noticeable from at least 15

meters away.

I was

excited to see my first Mauritiella

armata, a palm with the local name of Buritirana. It’s is related to

Mauritia palms (famous among birders for the species that depend on it) but is much slenderer and with this notably armored trunk.

I recognized

these fruits as Euphorbiaceae (see the three stigmas), but it took a bit of

searching to find its name, Mabea angustifolia.

One of the

most prominent shrubs here is a yellow-flowered member of the family

Malpighiaceae, probably in the genus Byrsonima.

Rather than offering nectar to pollinators, it’s much like our SE Arizona Krameria in having oil instead. I found

the Brazilian bee expert Felipe Vivallo to identify this huge and stunningly

patterned bee as Centris (Ptilotopus) americana (with Doug Yanega pointing me in the right direction with the genus). The

name in parenthesis is a subgenus, useful in understanding insect taxonomy where

genera can have hundreds of species.

And this is Epicharis (Xanthepicharis) umbraculata,

also in the subfamily Centridinae and also collecting oil (as well as pollen,

visible on the legs). Dr. Vivallo may be using these photos in an upcoming

article on the biology of this subfamily.

Other

special birds that we saw in this white sand area were Green-tailed

Goldenthroat, Pale-bellied Mourner, and a pair of these Spotted Puffbirds.

Perhaps the

most unexpected and exciting find was a pair of Ocellated Crakes in the short

grass pasture just outside the gate of the property. The nearest record is

about 600 km away, and we found them only when I got the strange urge to play

the song, even though I didn’t have the slightest expectation there would be a

response, which was indeed almost instantaneous, and only 50 meters away. We

actually saw one bird when I shone my green laser pointer over the location where I saw the weeds move, in order to get Jarmo

and Inger to look in the right direction. That didn’t totally spook the birds, and

with further playback I saw a rufous face and red eye peek out of the dense

grass less than a meter away from my feet. But typical for the species they stuck

to the densest grass and didn’t cross any of the open areas. My recordings also

appear on the Macaulay Library website.

We saw a few

butterflies, many which I recognized from Cristalino. This is the swallowtail Battus belus, which amazingly was caught

by the quick and patient six-year-old Alex with his bare hands. Will he become a politician, actor, entrepreneur, or entomologist?

This

clear-winged beauty is Haetera piera,

Piera Satyr.

Metalmarks

are my favorite: the tiny Sarota gyas

with the furry legs…

…and Mesosemia philocles, sometimes called an

“eyemark.”

But even

skippers can be colorful, such as this Pythonides

jovianus, Variable Blue Skipper.

We saw very

few moths this time, not only because it has been very dry, but also during the

full moon porch lights tend to not attract as many insects. This sphingid is Callionima parce, Parce Hawkmoth.

This is a

silk moth, Therinia buckleyi, which

wasn’t at the lights at all but resting during the day on a leaf in the understory.

This one is

a day-flying metalmark-moth Hemerophila

sp., in the family Choreutidae.

I went out

at night three times, and during the first walk Jarmo and I found this Corallus hortulanus, Amazon Tree Boa. It

started striking blindly the moment it sensed my infrared signature from about

3 meters away, so I didn’t even try to pick it up (not that I haven’t been

bitten with little ill effect by several wild boas over the years); the traces

of DEET on my hands probably wouldn’t have done it much good anyway.

I took the

whole family including the kids on a short night walk to see if a tarantula was

out of her burrow, but we first stopped to marvel at a long and very busy trail

of this army ant Eciton sp. probably E. hamatus.

I actually

saw but was not able to photograph one of the parasitic silverfish, different

that the one I had seen with E. rapax inSE Peru last year.

The

tarantula was out, but not very far out of the burrow, and not for long, as

they have many possible predators and retreat at the slightest tremor. This is

probably in the genus Acanthoscurria,

but Google searches on tarantulas deliver so much noise it’s hard to get any

good identification information. Species limits are probably not very well

known here anyway, considering that only just this year was the common genus Aphonopelma sorted out for North

America.

On one short

night walk I took on my own, I came across this very small tarantula, with a

body only about 3 cm long.

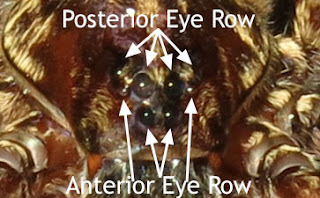

Judging from

the eye arrangement, this is a wandering spider, family Ctenidae. Its rather

slender appearance had me thinking it was a wolf spider (Lycosidae) or a

prowling spider (Miturgidae), so it was good I got some shots of the eyes.

This appears

to be Micrathena cyanospina, an orb

weaver (Araneidae), though I did not detect any blue tint to the amazing, long

spines on the abdomen.

This is the

very widespread but always fascinating Araneid, Nephila clavipes, the Golden Silk Orb Weaver. The yellowish tint to

the silk here is real.

The way it

holds it legs, and then finally the eyes, convinced me this colorful thing was

a crab spider, family Thomisdae.

After our 10

days of Amazonian birding and natural history fun, we headed back to Alta

Floresta via the Teles Pires ferry for our flight back to Cuiabá. And then onward to the Pantanal.